On Measurement, Part I

I am hoping to begin a series on measuring systems in a general way, and offer a defense of the imperial system in a specific way. Bear in mind, dear reader, that the defense of a thing isn't necessarily the attack of another (though in the current climate it's hard to see the two options as anything but synonymous). The advice that "the best defense is a good offense" is often ill-fated device. All that to say, that I am not keen on attacking the metric system. Calm down, there's no need to start slinging mud.

Folks debate over the metric and imperial systems of measurement like they do over Ford and Chevy. Now, I enjoy a good American truck debate as much as the next guy, but I fear that this rival brand mentality hinders a discussion regarding systems of measurement. I believe that a false tension exists between these two schools of measurement. Instead of viewing metric and imperial as rivals competing for the same turf, perhaps there are good reasons to view them as complimentary systems serving different needs. At any rate, that is the task I set before myself.

A proper understanding of these measuring methods origins I think shall shed some light on why they differ and why it is okay to hold onto both. Arriving on the scene rather late, the metric system has certainly made up for lost time and now is used the world over. A child of the modern project, the metric system grew up to meet the needs of rigorous scientific research. This is not to say that scientific inquires were non-existant before the coming of the metric system and the modern project! Rather, for the first time, scientific research began happening on a global and cohesive scale. Enter the metric system. Operating as a base-l0 system, metric grants its users a universal ease of mind. Converting between different units consists of adding or removing zeros. Working in fields rich with global dialogue, this exact and straight forward system cuts through the confusion created by a community bound not by region or language but by their work. I do not feel the need to list every instance in which the metric system works well, just know that I think that the body of modern science, fields of engineering, and various other sophisticated trades benefit from the metric system.

All of these scientific and technological fields of trades have exacting and precise natures. They do not rely on human scale and experience, which for their purposes is a rather good thing. But what about the areas of life that do rely on human scale and experience? Does it make sense to employ such a detached system?

Correct me if I am wrong, but I believe that the imperial system’s origins stretch back into a prehistoric times. That is to say that man began developing ways of measuring, on a human scale, before he began writing and leaving behind written records.

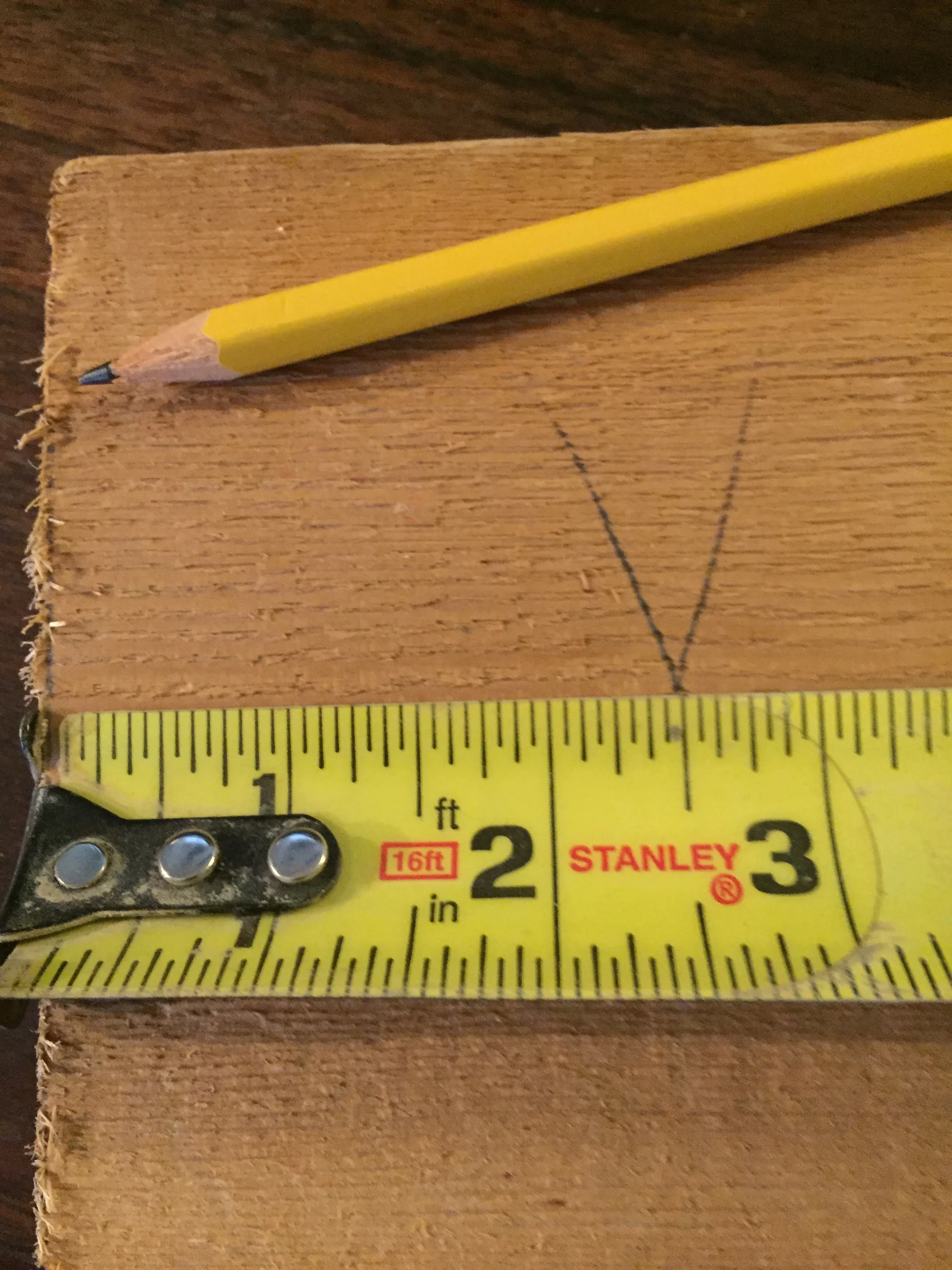

The imperial system is the current form of an old project. Not, I think old as in near death as some wish to believe, but old in the sense of orthodoxy. A system born out of the core and common place institutions of a community. The institution of the home, the art of cooking, and the job of a farmer etc. all rely on the human scale and experience to obtain their proper ends. Why does a cup make sense? Cup your hands together. Why is an acre an acre? Let a farmer give you one day’s work plowing a field and I’ll show you an acre of plowed land. Why is a league three miles? Walk for an hour and you’ll have walked a league. The point of these examples is to show how intimately connected the imperial units of measurement are to our human scan and experience.

I think that the relationship between the guitar and the piano is analogus to the relationship between metric and imperial. The piano strikes me as rather metric in nature, though I doubt that being able to play ten notes simultaneously makes it base ten. But, like the metric system, the piano provides a comforting sense of exactitude. There is but one place to play the note. Scanning over a piece of sheet music, a pianist rests in the fact that other pianists around the world will press the same keys as she will. There is but one right place to play a particular note.

A guitar on the other hand, a guitar has all the quirks of the imperial system. Looking at sheet music, a guitarist cannot always assume that a particular note is played on the same part of the fret board every time. It lacks that ease of universality but it possesses the ability to engage the unique flavor and experiences of the individual. What a guitar lacks in instant universal understanding it makes up for in local experience and expression.

The purpose of both the guitar and piano is to make music, but each one has a unique role within that common pursuit. Just so with metric and imperial. Both are systems of measurement with the purpose of aiding human work and understanding. Metric excels in various scientific and engineering pursuits when the imperial shines in the common and every day pursuits.

I am sure that folks can use the metric system in the tangibly human institutions, but would it not be better to employ the system designed on the human scale? Likewise, I am sure that you can use the imperial system in those institutions that exist outside of the human scale, but it would be better to adopt the systems designed for such pursuits.

A final word, regardless of how you come down on this issue, remember that at the end of the day we need to work well and to build well. America made it to the moon despite using imperial and Germans make good beer despite serving it in liters. On second thought, that might be the right course…